Thirsty new tech in the dusty Old Pueblo

Tucson’s next Motorola saga? … Sell the farm, buy a house … And stealing water from California.

Discussion of Project Blue has been percolating in Pima County for months.

We’ll direct readers to the Tucson Agenda’s Joe Ferguson and other sources for more detail on that saga and focus on the water dimension here, but to relay the story in brief:

The county announced an impending but non-specific economic development opportunity with some enticing job creation numbers in February, while citing non-disclosure agreements that prevented the release of more details.

By May, we learned it was a company “in the advanced and emerging technology industry sector.”

And by early June, we got at least part of the full picture.

That brings us to the Board of Supervisors vote last week on a petition to rezone and sell the land for the development for $20 million.

But what exactly is Project Blue?

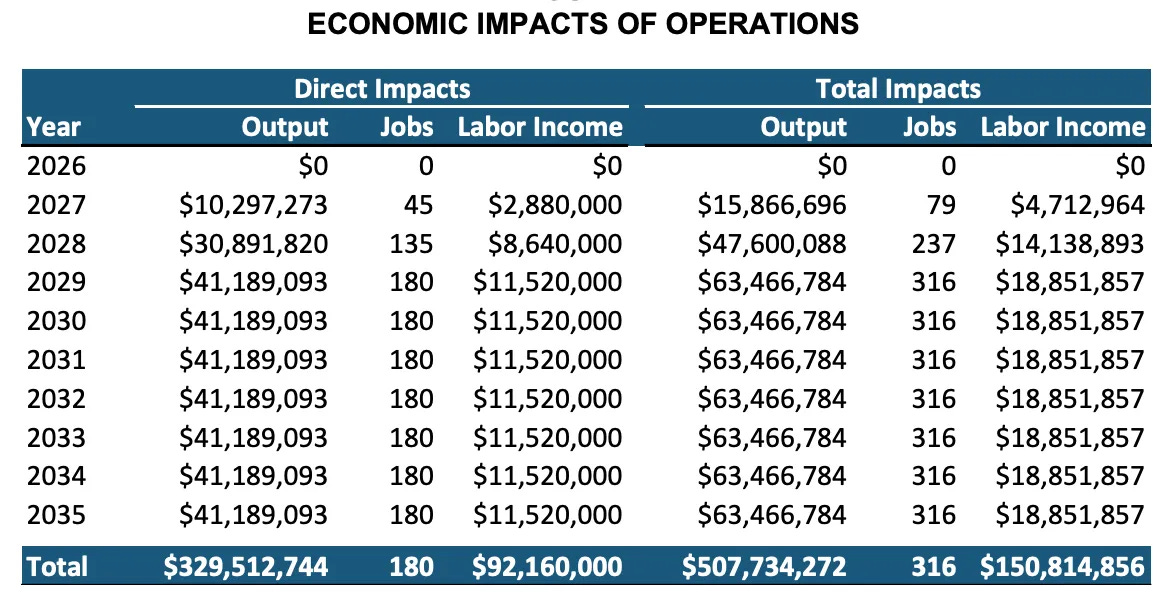

It is — or would be — a data center: three phases of construction beginning next year, billions of dollars, millions of square feet, up to 10 buildings, potentially hundreds of jobs, and, according to the developer, a neutral impact on the water supply.

It's also a “business proposition between Pima County and a buyer,” and a good one at that, Pima County Supervisor Steve Christy said during the June 17 hearing on the proposal. Here lies almost 300 acres of unincorporated, undeveloped land that “is not being used to its fullest potential,” he said. And here comes a buyer offering $20 million for the land and much more revenue down the road. The developer also says it’s receiving no special incentives from the city, county, Tucson Water, or Tucson Electric Power. (Data center equipment purchases are exempt from state and local sales tax for up to ten years, however.)

And outside of a trap and skeet shooting range and the adjacent county fairgrounds, there’s not much out there for the project to disturb (other than the desert itself, of course).

But this is just one way to look at the deal.

Upon completion, the data center would almost certainly become one of the largest — if not the single largest — customers of Tucson Electric Power and Tucson Water.

Especially in hot, dry environments, water is necessary to cool the server towers. Facilities in these environments tend to be less efficient, requiring more energy for cooling and other overhead costs than just for computing alone, but cheap energy costs still attract developers to the state.

We don’t know exactly what the facility’s consumption would look like. Its anticipated water and power consumption is under wraps in development agreements between the developer and the utilities. Larger data centers are known to use something like a 100 megawatt load and 1 million gallons of water a day.

But the companies behind the facilities don’t always report their consumption consistently. On a national scale, data centers consumed 2% of total U.S. electricity in 2021, and that number could double by 2030, according to an analysis of federal data from Bluefield Research.

And while most major American industries have reduced water withdrawals through the 2020s, this is not the case for data centers — withdrawals rose by 8.2% between 2020 and 2023. Only mining and the semiconductor industry — another darling of the Arizona private sector — have similarly increased consumption.

The developers and utilities maintain that the data center will use state-of-the-art technology to be as efficient as possible. On the water front, Project Blue pledges to be water neutral — using only reclaimed water and eventually recharging any net consumptive use.

“I’m very concerned about the idea of building it in a hot desert where a lot of cooling is going to be required,” Ed Hendel, who has an AI consulting business in Tucson, told the supervisors. “Project Blue claims to be water neutral or even water positive. Google’s data centers use net 5 billion gallons of water per year. And Tucson has a hotter climate than any of their existing data centers. Project Blue will be one of the larger data centers by industry standards. It’s promising more water efficiency than smaller campuses in cooler climates. That is an extraordinary claim that requires extraordinary evidence.”

So what’s the evidence?

Project Blue’s water commitments fall in three buckets:

It’ll use reclaimed water.

The company is investing in water infrastructure to replenish water losses.

And it’ll employ “industry-leading” technology that allows the cooling system to operate with only “minimal water and outside air” during cooler months.

Making good on these commitments requires constructing an 18-mile “purple pipe” extension that will bring reclaimed water to the area, which currently only has access to potable water. (A purple pipe, in water parlance, is just a pipe that conveys reclaimed water.) The developers are also promising to build a new 30-acre recharge facility.

There will be a period after the data center comes online and before the water infrastructure is completed. The developers say they will be able to use a limited amount of potable water per the agreement with Tucson Water during this interim, though it’s not clear exactly how long this period would last or what enforcement mechanisms exist for ensuring the developers make good on their claims.

These kinds of promises aren’t unheard of.

In fact, more and more data center developers are making significant local capital investments to offset water and energy consumption, per Amber Walsh, an analyst with Bluefield Research. Microsoft is rolling out data centers that use “chip-level” cooling to cut down on or even eliminate water consumption for cooling, including in Phoenix.

Amazon has helped finance purple pipe construction in Loudoun County, Virginia, another data center hotspot. Google contributed $6 million to an $8 million water infrastructure project in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

But the companies don’t always keep their promises.

A news outlet in the Netherlands discovered that a Microsoft data center in North Holland used 84 million liters — about 22 million gallons — in 2021, a year when even the suboceanic Netherlands was experiencing heat-induced water shortage. The company had previously said it was only using between 12 and 20 million liters a year.

“They fund the pipe distribution expansion, any treatment upgrades,” Walsh said. “It isn’t uncommon for these big tech players. But it’s really just for their benefit.”

It’s also a bit of a fallacy to think of anything that uses water as, well, water neutral.

And even if we assume the cooling system uses zero water, power generation still requires water, and lots of it. Just as aquifers are connected beyond borders, it’s important to look at water consumption in the context of the whole supply chain.

“You have to be careful in how you think about it in terms of water,” said Kathryn Sorensen, director of research for the Kyl Center for Water Policy and former director of Phoenix Water Services. “They’re obviously going to use water. They’re going to follow the laws of physics.”

And the promises to use reclaim are great, she said — but it’s up to the community to determine whether this is the best use of the reclaim. Cities like Phoenix have generally avoided constructing purple pipes for industrial use of reclaimed water in favor of banking the water and exchanging it for potable water or treating and drinking it.

“It’s great that they’re not going to use groundwater,” she said. “But is there a higher and better use for that reclaimed water? That’s the real comparison.”

A note about the climate

Numerous public commenters raised concerns about the siting of a data center in the arid Sonoran Desert. But as the Water Agenda and others have reported previously, Arizona is actually an attractive data center destination, and not just for its lenient taxes and business-friendly corporation commission.

“We are bastions of climate stability,” Sorensen said.

Hot and dry? A company can plan for that. Earthquakes, tornadoes and floods? Less so.

Water is generally a second-order concern for data center siting, Walsh, of Bluefield, said.

“They more care about whether we can provide continuous operation for the data center,” she said.

A tricky calculus

Tucson has lagged far behind Phoenix — the country’s second largest data center hub — and other central Arizona cities in adapting to the data center revolution.

Some anxiety about Tucson missing out on the next great wave of industry was palpable in the hearing room last week.

“I want to be on the right side of this opportunity,” Christy said.

Christy said the city should be wary of reliving what he called "the great Motorola fiasco."

In 1970, Tucson was in talks with Motorola over the potential location of a semiconductor plant in the city. Residents of neighborhoods in the city's northwest side, where the plant was to be built, pushed back on the plan, and the city rejected the necessary zoning petition. Further discussion with the company later in the decade yielded no deal. The company had become "leery" of the city, the Arizona Republic wrote in a 1978 piece. Ultimately, another cowtown benefited from the largesse of the company's semiconductor fabrication unit — now a tech hub you might have heard about called Austin, Texas.

In sum, city and county officials are in a tough position when faced with decisions like these.

Private sector investors want dependability, access and a certain extension of faith. But while data centers involve huge amounts of up-front construction jobs, their ongoing contribution to area employment is less significant.

And of course, there are the environmental concerns.

“There is pressure for cities to not appear to be anti-development in general because jobs and tax revenue are a real thing,” Sorensen said. “If you get a reputation out there of like, you’re impossible to do business with, that might foreclose the opportunity for future development.”

This tension was embodied in the vote of Rex Scott last week. He “enthusiastically” supported the proposal. But he acknowledged that the vast majority of constituents he’d heard from opposed it.

"Plans and promises have been made that, if they are fulfilled, could make this project a model for how to balance economic development and environmental protection," Scott said. "We have to do everything that we have planned and promised. To do otherwise will not only diminish any economic benefits that this project may bring, it will cause people to lose trust in government. It could also cause harm to this place we love and call home."

The two "no" votes came from Supervisors Jennifer Allen and Andrés Cano. Both supervisors echoed concern from constituents about the lack of transparency in the development of a project of this size — in particular, the lack of clear information about the facility's power and water consumption and the use of NDAs to keep the project out of the public eye for weeks before the hearing.

This type of secrecy is fairly common with large potential developers, Sorensen said. But that doesn't make it any easier to swallow.

“It is completely problematic. And in fact, the scope of Project Blue is still so murky and even from the little piece that we decided, it's still unclear,” Allen told the Tucson Agenda this week. “So there's the plot of land that we sold. The two to four data centers are on half of it. But then it's up to 10 data centers.”

There’s at least one other important wrinkle: Even with the county’s approval of the land deal, the city of Tucson still needs to approve a petition to annex the land for the development to go through.

Tucson City Council member Nikki Lee would represent the area to be annexed into the city. In a bulletin published Thursday morning, Lee said she was no enemy of progress but raised several questions about the environmental impact and economic benefit of Project Blue. And on a deeper level, she said policymakers and the public should have all the information necessary to make this decision.

"This may be one of the most significant economic development opportunities Tucson has ever seen, or it could become one of the most resource-intensive projects with limited long-term return," she wrote. "Either way, the public deserves transparency, and so do the elected officials at all levels who are being asked to make decisions with incomplete information."

The city council is expected to vote on the petition in August. But that timeline may still change.

Shortly after the vote last week, TEP announced it was seeking a 14% rate increase for residential customers. The developers and power company had assured the supervisors that the data center would actually protect residents from higher utility bills by providing consistent and significant revenue to the utility.

TEP maintains the timing of the announcement was coincidental. But it was suspicious enough that one supervisor who voted for the deal, Matt Heinz, said he would move for the body to reconsider its vote.

“I do believe them that they’ll bear the cost of infrastructure for their project,” Heinz told the Arizona Daily Star. “But then, minutes after we vote, 3-2 after two hours of discussion, this comes out. That chronology, that tick-tock, that temporal relationship is just untenable.”

(The logic here would be that TEP withheld discussion of the impending rate hike so as not to affect the supervisors’ vote on the data center project).

The legality of Heinz’s request isn’t yet clear. Generally, the county can’t reconsider a vote to ink a contract, but it’s possible the supervisors could reconsider their vote to rezone the land, which would similarly halt the progress of the development. Heinz still supports the project in concept, he told the Star.

But “maybe now we should have a month or two of discussions before we vote,” he said.

The so-called “ag-to-urban” bill emerged out of the House and Senate last week with support from both parties.

Under the bill, farmers with groundwater rights in Maricopa and Pinal Counties can exchange their rights for groundwater storage credits they can then sell to developers. The idea here is this would allow for residential development in the Pinal and Phoenix active management areas where, since 2023, “assured water supply” rules have blocked the development of for-sale homes.

Under this deal, when water rights change hands, a percentage of the rights are “cut,” so the plan is supposed to be a good deal for the aquifers as well.

The Legislature passed a similar bill last year, but it fell to a Hobbs veto. This bill has stricter limits about how far away the water rights can be relocated, responding to concerns about further groundwater depletion in Pinal County.

But there’s still a tricky conservation question here.

By law, groundwater depletion in the Maricopa and Pinal AMAs has to be replenished.

That’s a service provided by the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District, which uses the revenues from its members to purchase renewable water supplies and replenish groundwater on its members’ behalf. The ag-to-urban bill would open the door for more development in the two management areas, thus increasing CAGRD's groundwater replenishment obligations at a time of increased strain on the water supply.

Friends in high places: President Donald Trump nominated former Central Arizona Project manager Ted Cooke as the next commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Republic’s Brandon Loomis writes.

“He understands the dynamics across the basin in a way that will be really helpful in finding equity in outcomes from all of us in the seven states,” Arizona Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke told Loomis.

In sickness and in health: Buschatzke, who represents Arizona in Colorado River negotiations, has put forth a proposal to tie annual withdrawals from Lake Powell to a percentage of the “natural flow” of the river over a three-year period, rather than complex speculative water models. Some observers see the plan as a promising step toward breaking the deadlock between negotiators from the upper and lower basin states, Politico reports.

One "promising step" you could take to ensure the Water Agenda is sustainable is clicking this button.

And if gridlock continues?: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Acting Assistant Secretary for Water, Scott Cameron, has given the basin states until Nov. 11 to hammer out an agreement, leaving a couple of weeks of runway before a bill needs to get to the president's desk. What that means is complicated, writes Alex Hager for KUNC in Colorado, but it would likely involve major litigation, federal intervention and the potential draining of Lake Mead and Lake Powell at an even faster clip.

"That's a nightmare scenario," Anne Castle, former commissioner of the Upper Colorado River Commission, told KUNC. "And I don't think that the states or the federal government would allow that to happen."

A helping hand: Volunteers with the migrant advocacy organization No More Deaths placed 364 one-gallon jugs of water in the Altar Valley this weekend to aid migrants making the brutal crossing through the Sonoran Desert, per the Tucson Sentinel.

"This marks the start of the summer months when a large portion of the deaths happen in the desert," Ary Ospina, an organizer with No More Deaths, told the Sentinel.

The Trump Administration is showing interest in a proposal to pump up to 2.5 million acre-feet of groundwater from underneath the Mojave Desert in southeastern California and sell it to customers in Arizona.

The company pushing the proposal, Cadiz Inc., has long tried and failed to find customers within California, where the idea of pumping groundwater from the sensitive Mojave desert is a perennial political football, per Politico.

(A quick aside, putting my grad student hat on: As southern California was developed and urbanized in the early 20th century, developers and civic boosters pushed the idea that the area would be a Mediterranean-style oasis for Anglos. It’s funny — though perhaps not coincidental — to see remnants of that idea today in a company name like Cadiz, perhaps better known as the 3,000-year-old Andalusian port city).

Cadiz is presenting the plan as a way to support, rather than supplant, the management of Colorado River resources. And now the proposal has at least some buy-in from the federal government.

Last week, the Bureau of Reclamation announced it is entering into a memorandum of understanding with the developers of the project, called the Mojave Groundwater Bank, “to explore opportunities for technical assistance that can result in better understanding of the project’s potential benefits to the Colorado River system.”

The project is expected to include 300 miles of new and existing pipeline and break ground by the end of this year.

But there are more than a few wrinkles: the California Land Commission sent a letter to the developers this week urging them not to move forward with construction until they complete a lease application with the commission.

“Staff also feels the need to reiterate that any attempts, by Cadiz, to use the Northern Pipeline without Commission authorization would constitute an illegal use of state land and could result in significant litigation,” the commission wrote.

The proposal has also generated major blowback from environmental groups.

“It’s not surprising that an administration that wasted over 2 billion gallons of water under the guise of wildfire response thinks it’s a good idea to overdraft a desert aquifer that supports federally protected land,” Neal Desai, the senior program director for the National Parks Conservation Association, told Politico.

It’s not clear if any Arizona customers are already lined up for the water.

Either way, I can’t help but feel skeptical. Despite the novelty of the idea and the insistence from Cadiz that the project constitutes “a historic step toward solving the American Southwest's water crisis,” this smacks of the old ways that got us into this mess — moving earth and wrangling the desert to fulfill utopian visions of growth that somehow won’t tax our water resources.

On a more practical level: Arizona uses about 7 million acre feet of water a year. This aquifer under the Mojave might have as much as 2.5 million acre feet. I’m not sure Arizona’s vulnerable position in Colorado River talks (or animus toward Californians) justifies pillaging the Mojave for less than a half-year’s supply of water.

We know, at this point, that we need to use less water. Simply moving it around while maintaining the same growth will leave us only with more troubles.

"Either way, I can’t help but feel skeptical." No kidding. This "plan" has been around for a while. Probably be around for a while longer. If Motorola would have located their facility down near Hughes, Raytheon, and the airport...Tucson could have been Austin. BTW, the Motorola facility in E. Phoenix is a persistent Superfund site. One reason for closing East High School. Project Blue deserves a lot more scrutiny.