water crisis × housing crisis = ?

Crisis vibes … The rock, paper, scissors policy game ... And Phoenix becomes Atlantis.

Everything is a “crisis” now. It’s the border, opioids, climate, energy, inflation, mental health…

We’re in our Crisis Era.

And in Arizona, we have two crises in competition with each other.

Water and housing.

Collapsing groundwater, controversial policies, and an insatiable housing market have led to permit freezes, lawsuits, and a question about Arizona’s future.

What’s more important — rooftops or running taps?

The Housing Agenda

Back in 2010, Arizona’s median home price was around $138,000 and the median household income was $46,900.

Today, home costs are at $425,000 and incomes are at $76,900.

Home costs: up 300% 📈

Incomes: up 160% 📈

Why the differential?

Multiple factors contribute to soaring prices.

A decade of rapid population growth in Arizona put a lot of stress on the housing market.

And most of Phoenix’s newcomers are transplants from Seattle, Los Angeles, and other metro areas with higher incomes, and can outbid locals in the marketplace.

Investors are willing to pay more for homes than consumers. In 2000, investors were buying 7% of homes in the US. Today, it’s at 17%.

And Phoenix is one of the leaders in this trend, with investors now buying 20% of homes and flipping them at 37% premiums.

It’s worse with rentals. In 2001, deep-pocketed corporations owned 18% of rentals in the US. Today, it’s 50%.

Then add mom-and-pop investors buying up real estate for Airbnb and VRBO rentals. That doesn’t help.

More population, more investors, more demand — this drives up prices.

But so does a shrinking housing supply.

In 2010, 16% of Arizona’s housing stock was for sale. It fell to 8% by 2022.

The rate of home construction has been trending up, but not enough to keep up with demand.

Meanwhile, homeowners don't want to put their homes on the market because interest rates are still high.

And Phoenix ranks #1 in the build-to-rent industry — 11% of new builds aren’t even for sale.

But the most popular targets to blame for the housing deficit?

NIMBYs and regulations.

Cities and neighborhoods often protest increased housing density — locals don’t love more people, more noise, more buildings on the skyline, higher local prices — so the zoning requirements get tightened up.

There’s already a backlash.

Enter the Casitas law. Enter the YIMBYs boosting high-density urbanism.

Arizona is being pulled in different directions by desires for growth, affordability, and quality of life.

But to understand why home builders filed a lawsuit against the state in January, let’s pivot back to the 60s, when water entered the regulatory equation.

Thank Don Bolles

It’s 1967.

The Arizona Republic gives the front page to Don Bolles for eight consecutive days where he unravels the state’s biggest land fraud scheme.

Premier huckster Ned Warren was buying up dusty properties and selling ‘em to folks sight-unseen. Sometimes, he’d sell the same property to multiple buyers.

The dreamers thought they were getting a slice of Arizona paradise. Instead, they got roads to nowhere and houses with no water.

It was a bad look for Arizona.

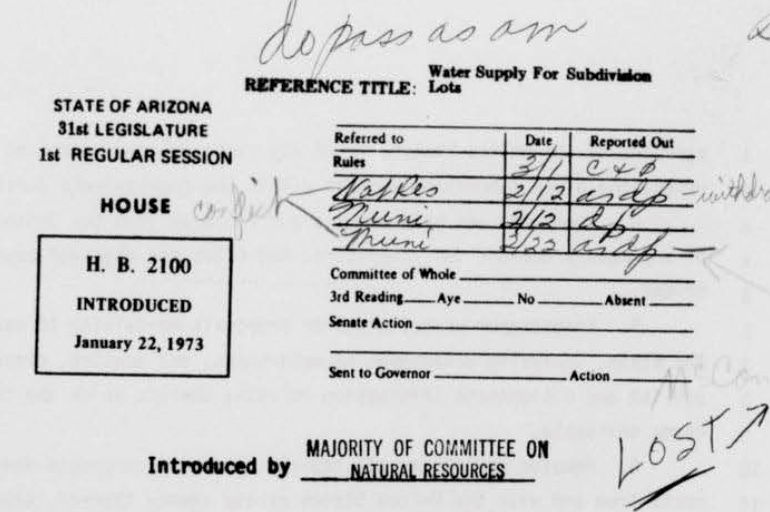

Lawmakers finally did something about it in 1973. House Bill 2100 required subdivisions to prove they had an “adequate water supply” before the homes could be sold.

This “emergency measure” flew through the Legislature with near-unanimous approval.

But what did “adequate” mean anyway?

In 1978, the state’s Groundwater Management Study Commission found the ‘73 law lacking clarity and doing little to curb housing development in areas of heavy groundwater declines. They proposed a strengthened policy, which became law as part of the Groundwater Management Act adopted two years later.

This new “100-year assured water supply” rule says if a development’s groundwater source is projected to drop below 1,000 feet from the surface over the next century, it’s a no-go.

And here we are today — looking 100 years into the future, seeing that we’ll be short on water in the Pinal and Phoenix AMAs.

One Hundred Years of Attitude

Not everyone agrees with the 100-year rule these days.

“Why is it 100 years?” asked Senate President Warren Petersen during an AZCentral podcast interview. “You don’t go to the gas station and buy 100 years of gas.”

Hmm.

We’ll have to forgive Petersen for not realizing Arizona doesn’t have magic ‘water stations’ to refill our aquifers whenever needed.

Speaking to the Republic’s Ray Stern on the issue, ASU water expert Sarah Porter said:

“In the minds of the greatest water planners and industry leaders, 100 years was the right time frame. … New water-supply projects have very long timelines because of the vulnerability of cities and how devastating it could be for a city to have a serious water shortage.”

Anyway, Petersen’s comment was responding to the ADWR’s 2023 decision to halt certificates of “assured water supply” for new developments in the Phoenix AMA — which means a lot of in-progress developments are now on ice — $8 billion worth, one real estate insider told us.

As a real estate professional himself, maybe Petersen finds these pesky consumer protections to be bad for business.

So why did ADWR freeze developments in Phoenix?

In her first month in office, Gov. Katie Hobbs had the Department of Water Resources (ADWR) publish a groundwater model for the Phoenix AMA which, she said, former Gov. Doug Ducey had instructed the agency to keep hidden.

"I do not understand, and do not in any way agree with, my predecessor choosing to keep this report from the public and from members of this legislature. However, my decision to release this report signals how I plan to tackle our water issues openly and directly," Gov. Hobbs said.

The model showed “unmet demand” for groundwater over the next 100 years, meaning water levels in some areas will drop below 1,000 feet.

And aquifer logic tells us that new water use in any part of a basin can, and typically will, impact groundwater levels elsewhere — so ADWR doesn’t want new housing to further endanger existing homeowners' assured water supplies.

ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke wrote an impassioned opinion piece on the Goldwater lawsuit earlier this week:

“ADWR is accused of acting aggressively in defense of Arizona homeowners who accepted the state’s most sacred pact with its homebuying residents: That if you buy a new home in a region protected by Arizona’s Assured Water Supply Program, you can count on an assured water supply.”

From a hydrological perspective, it could make sense for ADWR to freeze the developments.

We can’t steal from Peter to hydrate Paul.

But what about affordable housing and future growth?

The Home Builders Association of Central Arizona feels these are the more important problems to solve.

So they’ve teamed up with the Goldwater Institute — an elite corporate think tank — to file a lawsuit claiming ADWR’s “unmet demand” policy was adopted without following proper rulemaking procedures, that the concept is “made up”, and the rule is “invalid” anyway.

Optical Illusions

Let’s address the politics here.

ADWR’s “unmet demand” rule isn’t new. The Governor’s office sent us records showing the policy has been around since at least 2017. And it was first applied to the Pinal AMA in 2021 when Doug Ducey, a board member of the Goldwater Institute, was governor.

“The days of utilizing native groundwater for development in Pinal are over — it’s done,” said ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke at the time.

And he hinted at what was to come.

“Sooner or later, we’ll hit the situation in Pinal in every active management area,” he told the Capitol Times. “Hopefully folks in other AMAs have been paying attention.”

Despite the big wink from Buschatzke all the way back then, ADWR’s policy is being portrayed as Hobbsian overreach.

Goldwater couldn’t resist an opportunity to spin the optics.

But do they stand a chance in court?

Drumroll…

Goldwater’s 25-page lawsuit basically boils down to this argument:

Arizona law and code require ADWR to issue “assured water” certificates to new developments in the Phoenix AMA if they can pump assured groundwater for 100 years — no matter how bad the water levels are in other parts of the AMA.

When I pressed ADWR to give their legal defense for the freeze, they said they’ll be reserving their arguments for court.

So I decided to open up the Arizona Administrative Code and take a look for myself.

The AAC is the rulebook for state agency operations. Departments like ADWR often propose new rules to handle details the Legislature leaves open. Before a rule is adopted, it goes through public review, hearings, and approval by the Governor’s Regulatory Review Council.Goldwater is right. The Code doesn’t explicitly say that basin-wide water levels are the limiting factor for new housing certificates.

So this lawsuit will be a contest between administrative authority, legal interpretation, and common sense.

ADWR might be on the right side of history, but the courts will decide if they’re on the right side of the law.

If ADWR wins, the loophole remains closed, and new developments will have to find their water outside of the basin’s aquifer.

But there are other water-housing loopholes in the law.

Big ones.

Next week, we’ll look at how one of those loopholes is being exploited and turning Arizona into the “subscription housing” state.

Worlds are colliding in the Agendaverse this week.

The Arizona Agenda and Tucson Agenda want to give their readers a taste of the Water Agenda, A.I. Agenda, and Education Agenda, so they hosted some of our copy in yesterday’s editions.

You can read our Other News here (Arizona Agenda) or here (Tucson Agenda) to find out what’s been going on with:

The Rural Groundwater Act

The town of Salome’s water fiasco

A fight over the Grand Canyon

And more — like this story…

Drink the rich: Police are investigating a water heist at the Niagara Bottling warehouse in Mesa. Surveillance footage shows former employee Francisco Huerta using a forklift to load $100,000 of SmartWater and Kirkland water onto a semi-truck. 12News’ Kyle Simchuk reports Huerta was arrested January 29.

If only water were as plentiful as water news.

And the water stories aren’t going to slow down.

Our mission is to give readers safe voyage as Arizona’s communities navigate the complex path forward.

Feel free to pitch in some gas money for the journey.

And thank you — for sailing with the Water Agenda.

For today’s extra credit, we’ll be taking paid subscribers on a visual journey through Arizona’s future — if that future included magic “water stations” to meet all our water needs — with the state eventually facing an “oxygen crisis”.

Click here to see how Phoenix becomes the new Atlantis.

Outstanding newsletter! Great mix of technical detail, history, politics. Great insights into our most important/urgent natural resource challenge.

The third rail of conservation and the elephant in the room? We don’t have a shortage of water, we have a longage of people.

Fresh water is a finite yet recyclable resource—there is only so much water to go around, and our groundwater is being mined faster than it can be renewed. Human-caused climate change is having a negative yet unpredictable impact on precipitation, groundwater recharge, and the availability of surface water (e.g., Colorado River allocations).

In ecological terms, “limiting factors” affect the ability of an animal or plant species to thrive. Depending on the species, the limiting factor could be an appropriate climate, the availability of sunshine, food, water, or shelter, plus the absence of (or ability to survive) predators and disease.

Thanks to modern medicine and the ability to alter our environment to provide shelter and to produce and transport food, our human species has surmounted most obstacles to unlimited population growth, except for the fact that we have little or no control over the “limiting factors” that make our increasing population more contentious, expensive, and unsustainable.

So no, we do not have a shortage of water, and we do not have a shortage of housing. We have too many people seeking the things that are in short supply. Global population is now 8.2 billion, with 69 million more people being added every year. There has to be an upper limit to the human population—will it increase until we all suffer from disease, starvation, thirst, or violence, or will our urban planners seek to promote a sustainable environment by constraining growth through sensible zoning and regulation?

Zero population growth is essential for a sustainable future. More information on the impact of overpopulation on climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, natural resources, zoonotic diseases, and health, check out Population Connection (formerly Zero Population Growth): https://populationconnection.org