What’s the dam problem?

Do not wander off the dam tour … The earth’s new groove … And the woke agenda for clean drinking water MUST BE STOPPED.

Welcome back to the Water Agenda, folks.

If you ever find yourself talking about water all the time like I do, you’ll quickly realize that our everyday conversation is filled with water-themed turns of phrase, and unintentional water puns are unavoidable.

Allow me to illustrate:

As we get closer to deadlines for Colorado River negotiations, news feeds will be flooded with headlines about upcoming water reductions. State water managers face sink-or-swim decisions as Lake Mead hovers near historic lows. If Arizona doesn’t want to be left high and dry, she’ll have to make some concessions among the basin states. The decisions Arizona made 80 years ago had a ripple effect and now we’re stuck with junior water rights. The ship has sailed on merely treading water, and now we’re in over our heads as solutions dry up and…

You get it.

But today, as we do a deep dive on the Hoover Dam, we’ll be leaning into a water pun inspired by the classic 1997 film Vegas Vacation starring Chevy Chase. For some, the cheesy “dam” jokes and memes will be familiar, maybe nostalgic. For everyone else, this clip explains everything.

By the end of this dam tour, you’ll understand how the dam works and why it’s imperiled — and hopefully without boring your dam pants off.

The dam thing works!

At the time of its construction, the Hoover Dam was the most expensive water project in U.S. history and the largest concrete structure in the world. And if you’re like me, you’re wondering how this monolithic marvel could be constructed in the middle of a flowing river.

Well — it wasn’t.

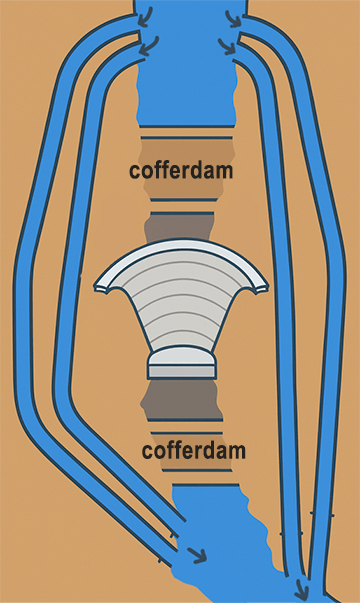

First, water diversion tunnels were excavated along the canyon. Then the rock excavated from the tunnels was piled into the river and fortified with concrete to create two temporary “cofferdams” — leaving a dry gap in the river where the dam could be constructed. It was completed after five years.

So, what about those four giant art deco towers sticking out of the water in Lake Mead? They’re called “intake towers,” and they channel water down under the dam and into the power-generating turbines, while regulating flow speeds and keeping out debris.

Water managers throw around a few critical terms when it comes to Hoover Dam. Here are the two big ones:

Minimum Power Pool (≈950 feet): This is the water level at which Hoover Dam can no longer generate electricity. The turbines can’t function without enough water pressure. That’s a big deal for cities like Las Vegas and Los Angeles that rely on the dam’s affordable, renewable power.

Dead Pool (≈895 feet): This is the doomsday line. At this level, water can’t flow through Hoover Dam at all. No more water to California, Arizona, Nevada or Mexico. The fact that we even talk about it seriously should raise some dam eyebrows.

In 2008, hedging against future lake declines, Nevada built a below-dead-pool intake system to deliver water to Las Vegas. You know… just in case.

Dam near empty

Lake Mead doesn’t have to hit dead pool for things to get painful. Under the 2007 Interim Guidelines and the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan, certain “trigger elevations” require mandatory water cutbacks to the Lower Basin states — Arizona, Nevada and California — and Mexico.

1,090 feet (Tier 0): The warm-up round. Arizona and Nevada take small cuts to slow Lake Mead’s decline.

1,075 feet (Tier 1): The first official shortage. In 2022, Arizona was out 18% of its Colorado River allocation.

1,050 feet (Tier 2): Deeper cuts for all except California.

1,025 feet (Tier 3): This is where all the Lower Basin states take hits — big ones.

You might have seen Lake Mead’s “bathtub ring” — the chalky mineral line on the canyon walls — which now stretches the height of a 15-story building. It tells a concerning story.

Lake Mead was riding high in the 90’s, almost at capacity, 1,214 feet above sea level. That didn’t last long. The Millennium Drought, along with overallocated Colorado River water supplies, dropped the lake by more than 150 feet. It was down to 1,040 feet by summer 2022, an all-time low that triggered Tier 2 shortage reductions.

After some unusually heavy snowpacks, Lake Mead regained some volume and now sits at the 1,063 mark, halfway between Tiers 1 and 2.

But the downward trend is not looking good.

Another dam problem

About 360 “river miles” upstream from the Hoover Dam is Glen Canyon Dam, which forms Lake Powell. It’s the Colorado River’s second-largest reservoir, and it has problems too.

In 2022, Lake Powell dropped to 3,522 feet, dangling a dangerous 32 feet above its minimum power pool. Below that level, Glen Canyon must rely on emergency water outlets — four big steel pipes that bypass the dam and keep water flowing downstream to Lake Mead.

Problem is, those pipes were never meant for full-time use. Worse, when the Bureau of Reclamation ran a “high flow experiment” in 2023, they found damage inside the pipes caused by water erosion, endangering their ability to handle emergency flows.

If Glen Canyon fails, no more water to Lake Mead. The Bureau of Reclamation launched an $8.9 million project to reline the outlet works with epoxy, but some experts argue that’s just a Band-Aid. Arizona and Nevada recently requested serious upgrades — maybe even new tunnels drilled at lower elevations — to guarantee future water releases.

What’s next for the dam nation?

The current operating rules for the Colorado River expire in 2026. Right now, states and the federal government are negotiating what comes next — a process that could reshape water policy for decades.

ASU’s Kyl Center for Water Policy just released a new paper called “Enduring Solutions on the Colorado River Part II.”

An excerpt:

“Absent Compact litigation or a ‘grand’ bargain, in a declining Colorado River system, Central Arizona faces near certainty that its water uses will be cut significantly on a near-permanent basis and will be cut even more (potentially even to zero) a significant amount of the time.”

The future of the river — and the 40 million people who depend on it — might come down to how quickly the states can adapt. Retrofit. Conserve. Compromise. Or… litigate.

Until then, we’re all just passengers on the dam tour.

If you enjoyed today’s tour, you can support the Water Agenda by buying a dam souvenir subscription.

As the world wobbles

The Southwestern U.S. isn’t the only place dealing with groundwater declines. Actually, the whole planet is feeling the subtle impacts. Compelling research shows that groundwater depletion and loss of soil moisture are causing the Earth’s rotation to wobble a little differently than it used to, and that groundwater moving into the oceans has caused sea levels to rise (slightly).

Some headlines on global and national groundwater issues from just the last two months:

Snowfall in the Hindu Kush Himalaya region is at a 23-year low, impacting several major Asian river basins and 2 billion people, and creating increased groundwater demands.

In Rajasthan, India’s only state without sustainable groundwater regulations, farmers are closing up shop as wells go dry.

In Brazil’s Verde Grande Basin, 74% of rivers are leaking water into adjacent aquifers because of heavy groundwater use for irrigation.

Turkey’s Tahtalı Dam reservoir has plummeted to 15% capacity, leading to increased groundwater pumping.

In Tehran, unregulated groundwater depletion has led to 14 inches of land subsidence per year.

Australia is facing upcoming water regulations as groundwater levels continue a 20-year decline.

In the U.S., Southeast Georgia’s declining groundwater sources have led communities to start using more water from the Savannah River.

In the U.S., ongoing groundwater declines are reported in Georgia, Texas, Florida, Oregon, California, Nebraska, Hawaii and other states.

If there’s a silver lining, it’s that the whole world will be working on advances in water recycling technology — and that can go a very long way in solving problems here in Arizona.

Save water, save money

Water rate hikes are being explored in Avondale, Peoria and Scottsdale as utilities address aging infrastructure, inflation and drought-related water shortages. Earlier in the year, Buckeye, Gilbert and Tempe had already had their rates increased.

In Pima County, Global Water Resources has secured approval for a phased rate hike in Sahuarita. Beginning May 1, customers will see a 50% increase, followed by two additional 25% hikes, with the added revenue funding local infrastructure improvements.

How to save money as water prices go up? Get rid of grass and collect rainwater.

Many cities, like Tucson, Mesa and Phoenix, provide rebates for turf removal and xeriscaping. Cities also have guides for rainwater catchment and green stormwater infrastructure, see: Mesa, Chandler and Phoenix.

Tucson offers rebates for rainwater systems and Watershed Management Group offers classes on how to use the rebate program. Tucson also provides a low-water landscaping plant guide. You can Google to see if your city offers financial incentives for water conservation, which would also cut down your water bill.

City governments are not offering incentive programs for independent journalists to let you know what’s really going on with water.

So you’re gonna have to help out with that.

The Good, the Bad, and The Smelly

Welcome back to Extra Credit, supporters of the Water Agenda.

This month, a project funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation made a major breakthrough on technology that can remove 90% of PFAS (forever chemicals) from groundwater.

And because Trump wants the U.S. to have “the cleanest air and crystal-clear water,” we’re sure to see that technology get further developed and potentially scaled out for all the high-PFAS water supplies in the U.S. that are endangering human health. Right?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Water Agenda to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.