Rural Arizona’s Watershed Moment

The third Act … An unlikely coalition … And everything dissolves in water.

June 12, 1919: Arizona adopts its first comprehensive water management policy, the State Water Code.

June 12, 1980: Arizona’s historic Groundwater Management Act is adopted.

June 12, 2025: ... ???

Last week, Gov. Katie Hobbs held a press conference announcing the Rural Groundwater Management Act, a comprehensive and aspirational bill meant to finally address Rural Arizona’s longstanding groundwater problems.

Unlike the bill’s 2024 predecessor, which never got a hearing, this version has been elevated to ‘Act’ status — signaling optimism among its supporters and their readiness to give it a strong public campaign push this year.

If her efforts succeed, Hobbs would be building upon a bigger legacy in Arizona, where Democrats and Republicans roll up their sleeves and sweat through negotiations for the sake of protecting our water resources.

In 1980, after years of legislative gridlock, Gov. Bruce Babbitt stepped in to finally get the Groundwater Management Act across the finish line by organizing a closed-door summit of lawmakers and stakeholders.

Former lawmaker Tom Chabin, then a representative for the Hopi tribal government, and currently a policy advisor in Attorney General Kris Mayes’ office, attended the summit as an observer and gives this insight:

“The legislators didn’t have problems [at the summit]. It was the special interest stakeholders who had problems — often with each other. Every now and again, when something would melt down, everyone would go into recess. They’d stop everything and iron it out in sidebar conversations, and then come back.”

Old-fashioned compromise-making.

Will 2025 also see legislators and special interests managing to strike an accord?

Many are hopeful.

In today’s story, we’ll help you grok the shape and scope of the bill, why it’s being championed by a bipartisan coalition of stakeholders and officials, and a preview of the hurdles it will have to overcome.

And next week, we’ll take a closer look at a lawmaker who will decide the bill’s fate this year.

The Water Front

I wouldn’t bother to write this story if the Rural Groundwater Management Act didn’t already have a necessary bipartisan alliance supporting it, including rural officials and stakeholders.

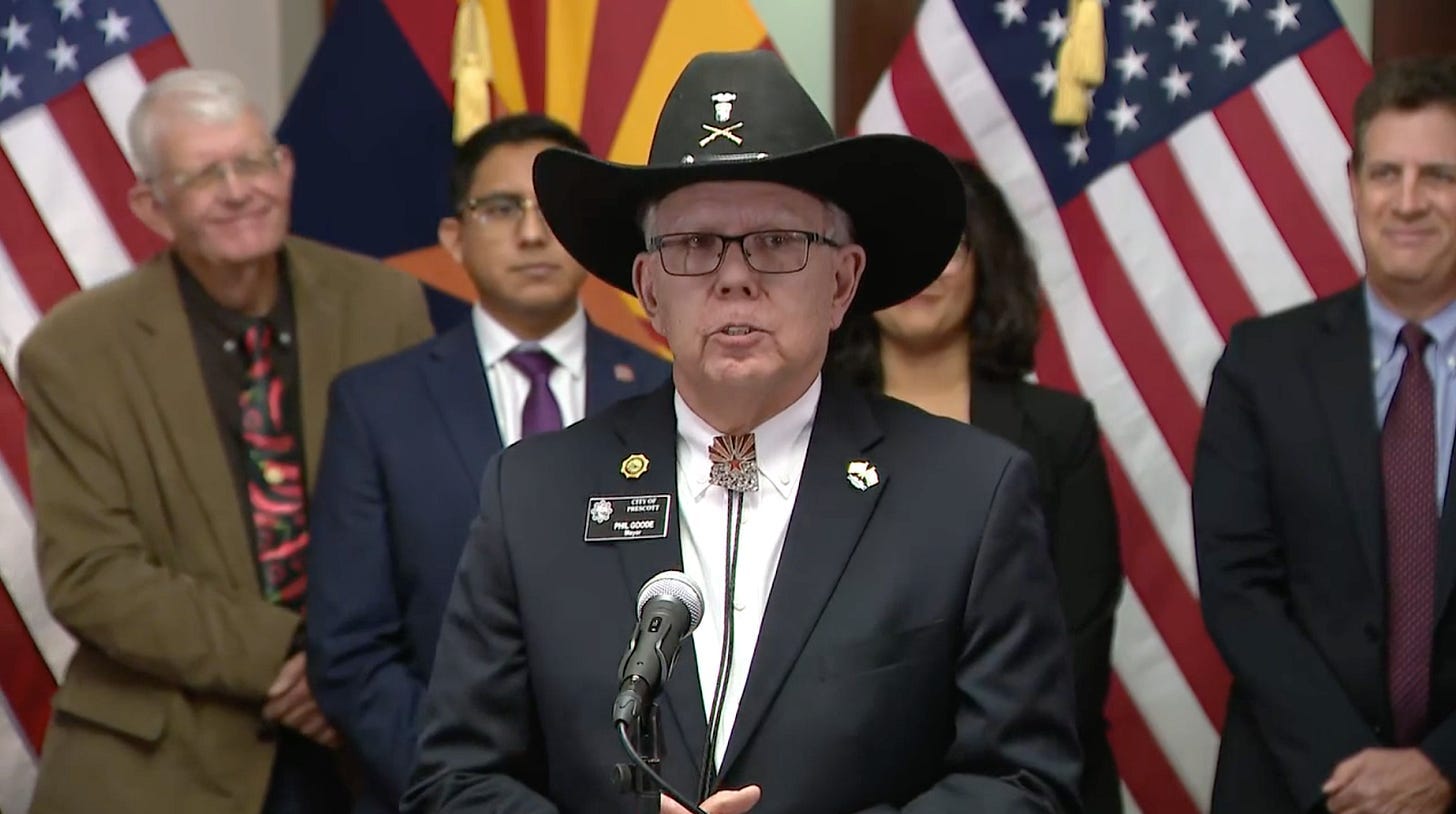

At last week’s press conference, the Republican entourage included:

Travis Lingenfelter, Mohave County Supervisor

Holly Irwin, La Paz County Supervisor

Phil Goode, Prescott Mayor

Ken Watkins, Kingman Mayor

Cherish Sammeli, Kingman Vice Mayor

“Make no mistake: I am a conservative, active Republican. But this issue is not a partisan issue. Last time I checked, there is no Democratic water and Republican water,” said Goode, the Prescott mayor.

The Democratic entourage was slightly larger:

Governor Katie Hobbs

Sen. Priya Sundareshan,

State Senate Minority LeaderRep. Oscar De Los Santos,

State House Minority LeaderRep. Chris Mathis

John Fanning, Santa Cruz County Supervisor

Patrice Horstman, Coconino County Supervisor

Nikki Check, Yavapai County Supervisor

Willcox Mayor Greg Hancock and Willcox farmer Ed Curry were also there in support of the Act — and support from Willcox leadership is crucial because the bill would repeal the Willcox Basin’s recent Active Management Area (AMA) designation and redesignate it as a Rural Groundwater Management Area (along with the San Simon Valley, Gila Bend, Ranegras Plain, and Hualapai Valley Basins).

But rural Republican leaders will still have to work hard to ensure Republican support for the Act’s mirror bills, SB1425 and HB2714, in the Legislature.

“Water is not a partisan issue — it’s a community issue. I urge all legislators to work collaboratively with Governor Hobbs to find a solution,” Willcox Mayor Greg Hancock said at the conference.

Build the water wall

It’s a lot easier for Republican leaders to champion “sustainability” policies when the narrative is less “save the planet” and more “stop the out-of-state and foreign water pirates.”

“Over the past decade in Walapai Basin … we've had Saudi, United Arab Emirates, and central California corporations — who are no longer permitted to over-extract groundwater where they are from,” Lingenfelter, the supervisor from Mohave County, said at the press conference.

It’s well known that Saudi-owned megafarm Fondomonte is in Arizona because their country outlawed the extraction of groundwater for growing alfalfa, the crop they feed their dairy cows. They now grow and export alfalfa — or “virtual water” — from Arizona to Saudi Arabia.

“According to the ADWR, over 70% [of the groundwater deficit] is attributable to the international and out-of-state interests,” Lingenfelter continued.

Unlike the border wall, fortifying the defense of Arizona’s groundwater isn’t a partisan issue. No good Arizonan can stand for California helping themselves to our limited groundwater supplies.

Hobbs added her voice to the chorus:

“I’m not going to sit by and let out-of-state corporations exploit our resources,” she said at the conference.

But how would Rural Groundwater Management Areas solve Arizona’s groundwater problems?

And how are they different from AMAs?

“Local control”

In 2022, one of the biggest problems voters had with the Douglas and Willcox AMA initiatives was the lack of local oversight in the AMA system — the governor and Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) have all the authority.

While every AMA does have a five-member Groundwater Users Advisory Council or “GUAC”1 which meets regularly with the ADWR, the GUACs have no decision-making power. And there are no criteria for whom the governor appoints to these councils.

Rural Groundwater Management Areas (RGMAs), by contrast, would create RGMA Councils with the authority to choose their preferred conservation goals and design unique groundwater management programs they feel are appropriate for their local area.

RGMA Council members would still be appointed by the governor, but with certain requirements:

Four of the five members must be residents within the RGMA.

Four of the five must be chosen from short lists provided by each of the state House and Senate party leaders.

Council membership must include stakeholders from local agriculture, industrial, and municipal water sectors.

Actual protection

The Initial AMAs established in 1985 were supposed to fix groundwater declines within 40 years.

But here we are, 40 years later, still overdrafting our aquifers in Central Arizona.

This is partly because AMA laws lack clear instructions on how to reduce overdrafts, and the ADWR has avoided sticking its neck out to create protective and meaningful reduction programs.

The Rural Groundwater Management Act fixes this.

After an RGMA is designated, its first 10-year Management Plan requires a 10% reduction in groundwater use by commercial water users. And subsequent management plans would adjust those reductions based on the progress made toward eliminating the overdraft.

Moreover, RGMA Management Plans would be required to include:

“A schedule for annual conservation reductions in groundwater use for all uses of groundwater pursuant to certificates of groundwater use, other than municipal uses.”In other words, RGMAs will need to have clear and explicit programs that actually get the job done.

$

And there’s always the question of money.

RGMAs would create a legislative appropriation fund, and allow the RGMA Council to enact fees for commercial groundwater withdrawals. AMAs don’t have these perks.

Collected fees would go toward conservation programs in the RGMA which, the bill says, may include:

Voluntary land or water use agreements with landowners or water users

Stormwater retention and recharge incentives

Low water use development incentives

Incentives for low water use practices, fixtures or landscaping

Irrigation efficiency, conservation and low water use agricultural incentives

An ideal outcome might see the largest RGMA water users paying fees which help smaller farmers and municipal providers to conserve more water.

Sounds pretty good.

But will it float?

During her press conference last week, Hobbs optimistically reported:

“I actually had a meeting with Representative (Gail) Griffin yesterday. I would characterize that meeting as positive and, I don't want to put words in the representative's mouth, but I feel that we both left the meeting with at least a basic agreement that something needs to happen this year.”

But this kind of agreeable interaction is typical of Rep. Gail Griffin, Arizona’s “gatekeeper” of water policy.

Last year, former lawmaker Regina Cobb (R-Kingman) had this to say about working with Griffin:

“She was very nice, listened to me, but never once heard my bills … I would take her a bill and say, 'we've got to have some kind of groundwater legislation in Rural Arizona — help me with this, figure it out. What's doable, and what's not doable?' And she would say it every year: 'Let me read it, let me see what I could do with it,' and then she'd throw it in the drawer. She wouldn't look at it.”

So, it’s not super promising to hear that Hobbs and Griffin merely had a friendly chat.

Back in 1980, the really big carrot that brought everyone to the Groundwater Management Act negotiation table was federal funding for the CAP canal, which would finally bring Colorado River water to Central Arizona.

No big carrots exist this time around.

Instead, Hobbs has been wielding a big stick emblazoned with the words: I Will Designate AMAs In Rural Arizona Until We Figure Something Out.2

Last year’s Willcox AMA designation got the attention of some key players in the water wars. And the threat of more AMAs might be enough to see the bill through.

We’ll find out soon enough.

In next week’s Water Agenda, we’ll be looking at…

How Gail Griffin earned nicknames like “the Queen Bee of Water”

The battles she fought with her Republican colleagues

What happened when a frustrated lawmaker added an entire bill to one of Griffin’s bills as a “hostile amendment”

How Griffin keeps getting elected as chair of natural resource committees

Her other adventures in lawmaking

And more

I only remember three things from my Ninth Grade Oceanography class with Ms. Mosher:

Water beads up around its edges because of electrostatic bonds between the hydrogen and oxygen atoms of neighboring water molecules.

Ms. Mosher’s pink visor with pig ears and tail which she wore during our class’s boating field trip on the Chesapeake Bay.

Water is known as the “universal solvent” because it dissolves more substances than any other liquid.

Water is powerful stuff.

But can it dissolve ideological tensions and stakeholder stalemates?

I think it can.

Sincerity is dangerous in politics. It exposes contradictions and complexity. It forces policymakers to acknowledge trade-offs, shortcomings, and nuanced stances that don’t fit on a campaign sign or in a tweet.

But that’s what’s happening right now in Arizona’s groundwater story. People are making some space for sincerity and cooperation. Because the aquifers don’t care about polling data. And the people who farm, cook, and survive with this water — they don’t care who leads the fight to protect it, as long as the job gets done.

Maybe it’s about time that Arizona’s water policy reputation in the Southwest switches up from trailing behind to leading the way.

Some people certainly think so.

The GUAC acronym is pronounced goo-ak — not gwahk like “guacamole”.

And Hobbs had a big assist from AG Kris Mayes who brandished the ‘I Will Sue Corporate Agriculture Until We Figure Something Out’ stick.